Short Fiction

Read some of my short fiction

I’ve put a couple of stories here already of course, but some other places my short fiction has appeared:

I’ve put a couple of stories here already of course, but some other places my short fiction has appeared:

‘Dirty and Unclean’ – A story about wedding feasts and a girl who really doesn’t want to go out with the same old boring Jews was broadcast on Radio 4, and is sometimes repeated

‘Internal Investigations’ – A piece of proper sci-fi about a future where we augment our bodies was broadcast on the World Service and ought to be listenable-to here forever… I think.

‘Other People’s Gods’ – which is the story that was shortlisted for the National Short Story Award is available in their anthology and was published in Prospect

‘The Final Analysis’ – an old story of mine, but a good one, about crazy psychoanalysis, was in the UEA anthology

‘Rising’ – the most chick-lit thing I’ve ever written, about recovering from a relationship breakup via baking, is in The Best Little Book Club In Town anthology

I keep thinking I should collect some of my stories into a book sometime, along with some that have never been published! But publishers tell me that no one buys short stories. Could this be a job for… Kickstarter? Watch this space, I guess.

Together - a love story in nine friends

A love story in nine loosely-networked friends

A love story in nine loosely-networked friends

At the party, you level up. It is while you are talking to a new acquaintance. At least, you thought they were an acquaintance. But you tell them about your childhood, about your difficult relationship with your parents. You mention the things you feel you have to conceal about your life from your father and there it is, suddenly, a winking of stars around your new friend’s head. A musical chime. The other guests politely put down their drinks and applaud your achievement. While you’d been speaking, your acquaintance had pressed a particular patch of skin to indicate to the network that you are now a friend. Your 5,000th friend. You are popular. Everyone knows it. After the brief pause to celebrate your new status, you go on talking about the trouble you have understanding your past.

In your psychotherapist’s office, it’s considered good form to turn off all social networks. No one can tell whether you’ve complied, of course, not even the therapist, your professional friend. With broadcasts directly to the visual centres of your brain, input devices under your skin, and a soundstream that taps directly into the aural nerve, turning it off and on is as easy as a thought. She’d never know. Keeping them on is like lying to your therapist, though. You’re not going to be much helped by the process, she tells you, if you bring other people into the room.

It is peaceful to turn them off for a while. Many people have turn-off hours, or even turn-off days. Not every thought has to be broadcast. People are fond of repeating this mantra. It is a critique of others – of those people in those places – and a reminder to self. The very fact that it has to be repeated, of course, is a sign of how little it is understood.

It feels pleasant to remember that you are solitary, sometimes. Your therapist listens to your dreams – those cannot, yet, be broadcast on the network – and to you talking about how much you hate yourself. No one else will ever hate you quite as much as you do.

And yet. When you reach for a simile, it is not there. You want to consult the network. It is only with the greatest struggle that you persuade yourself not to do so. Your vocabulary is poorer without it. Your knowledge is diminished. Even your memory of your own life is richer and fuller on the network than any non-networked human could achieve.

“Don’t you think,” you say, “that the network could be a therapeutic tool, actually?”

There is no answer.

When you turn around and look at your therapist, you think that you spot the momentary rapid-eye-movement signalling that she is checking in with her own network. She denies this, when you ask.

You hold the baby of your childhood friend. You and the mother have known each other for nearly twenty years. The baby seems to smile at you.

“He’s just got wind,” the mother says. Nonetheless, you smile back.

“When are you going to settle down?” she asks. You say nothing.

The baby’s name is already registered on the networks, reserving a place for him when he is grown.

Babies do not have friends. Before a certain point – perhaps 12 or 18 months – babies are not aware that there is any separation between themselves and the world at all. It is only when they understand that other people have private inner experiences, that it begins to become meaningful to talk of them having ‘friends’. As soon as we realise that we are alone in our own heads, we begin to seek companionship.

It is an effort, to maintain the barriers between us and the world outside. That is why falling in love feels so good. Lowering the boundary around our carefully maintained ‘self’ at last is ecstatic. It has been some time since you last fell in love.

You surreptitiously check on the status of your 5,000th friend on the network but are disappointed: all the signs are that they are in a serious relationship. But the network tells you that an old companion is still single. The two of you have had an arrangement in the past. When you initiate contact, it is well-received. You meet up at your home in the middle of the afternoon.

You try to express your concerns about friendship, about the nature of social relationships, about the need for solitude, but although your friend is vaguely interested, that’s not what you’re there for.

“We’ve become a new kind of human,” says your friend-with-benefits, reaching a hand toward your thigh. “Homo Connecticus. It’s just the next stage in our evolution. Why look back?”

You’ve heard this argument before. Your friend has nothing new to say. And after all, you didn’t want to talk.

The afternoon passes pleasantly enough. You feel alone even when your friend is lying in the bed next to you. It is only switching on the network, feeling the buzz of chatter swarm over your body, that makes your loneliness recede.

The next day, you talk to your brother in Buenos Aires. Or perhaps Istanbul. Or Yokohama. It’s getting hard to keep track of where he is these days. And it doesn’t really matter. Wherever he is, his image is projected onto your retina, hooked up to your nerves. There are no more absent friends these days

“You’ve got to give up on that friend with benefits thing,” he says, “it’s doing you no good. You need a real relationship.”

Your muscles tingle with the relief of an unburdening conversation. You grin. You feel known, and understood, and cared-for. You feel companioned. You are entirely alone in your apartment, smiling into empty space.

The relationship between the mind and the body is problematic. The 17th century philosopher Descartes thought that they were separate and distinct entities. The body is a machine, the mind is its driver. Other philosophers have accused him of imagining a homunculus – a tiny man – inside the skull, examining inputs from eyes and ears and other senses, pressing buttons in response to make the body move. This position is philosophically unsound.

But it points to a certain kind of truth. We understand that there is a real, astonishing person inside each of the often uninspiring meat bodies we walk around in. We battle against prejudice based on physical attributes: skin colour, gender, age, height, disability, body shape. When over the centuries we have imagined heaven, we have often imagined it as a place beyond the physical, where pure thought and spirit are the only reality.

Your brother’s body is unimportant: it is his mind, or his spirit, or his soul, that has given you a hug. Surely this is the dreamed-of heaven.

You sink into a light depression. Nothing too extreme. You have bodily-status updates enabled on the network, though. When various electrical indicators drop below a certain threshold, the system posts a mood line. The network tells all your friends you are “a bit sad” and offers them various ways to comfort you.

A shower of virtual flowers, hugs and cat pictures begins to stream into the online inbox behind your eyes. Some cost your friends actual money – not as much as a cappuccino, but more than you might drop in the street without bothering to pick it up. You feel a little better.

Some friends – mostly those in the group you’ve labelled ‘real friends’ on the network – actually call to check in with you. You talk it out. They tell you this can’t last forever, that everyone goes through difficult times. They mention your parents and remind you how far you’ve come already.

Moods are contagious though. They’re meant to be. Ethnomusicologist Joseph Jordania theorised that the human ability to become lost in collective identity – often through dance or chanting – is necessary so that we can sacrifice ourselves to preserve the species. The very survival of the human race has sometimes depended on our loss of self. It is only very recently that we placed such emphasis on the identity of the self anyway. Perhaps it’s more natural to be ‘us’ than ‘me’.

Increasingly, like you, network users have enabled sensory feedback on other people’s statuses. The messages and moods of your friends are converted to sensations in your body. There’s a particular tingling pinprick that you’ve come to associate with unread messages, and a rushing sensation when your friends have mostly positive mood states. We have become one organism, feeling our moods together. An empathy machine.

So it is inevitable that when your mood drops, you lose a few fair-weather friends. Only those who cannot afford to feel that way today. They may be back, or if not their place will be taken quickly. You already have 5,050 friends anyway. You will not miss the dozen or two who let you fall into the blue.

However, there are certain people whose mood falls so low that they are defriended by hundreds, thousands of people. There’s no recovering from that. Terminal velocity. They still go to work, perhaps, have families or hobbies, but a catastrophic loss like that on the network is like becoming homeless. You have to start from scratch. But most people won’t trust you enough to let you begin again. A 30-year-old with no friends on the network is a weird and unsettling creature.

A day or two after your low status update, your 5,000th friend calls you on a private network channel. That relationship you thought you detected on the network has ended; this is dropped in casually into the conversation. You notice the casual-ness. The conversation is guarded, each of you attempting to be funny, excessively delighted to find that the other is amused by your witticisms. At least, you think your new friend is attempting to be funny, you imagine excessive delight. You are uncertain whether what you think is happening is happening.

You’ve misread the signals before and have been astonished by the devastation of realising that you were the only one who thought that certain messages were being given and received. If we were all supposed to be comfortable with our internal solitude, why would we be distressed by a misunderstanding? We want to touch the homunculus in the other’s skull.

Interactive forms tend to speak in the second person: “where do you want to go today?” “what are you doing?” “how do you feel about your father?”

In the network, you are constantly being spoken to. It tells you who you are, and what you are doing. “You are following Adrian.” “You hung out with Andrea.” “David has poked you.” You gave up control of your self-definition so gradually that you barely noticed it at all. You feel alright about the network. Are you being told that, or is it the truth? Is there a difference?

You are tightly coiled, churning with questions about your 5000th friend. Your therapist is out of town, as she so often is when you need her. You use the network’s built-in counsellor.

“How do you feel?” says the mechanized human, the imaginary friend.

“Sad,” you say. “Worried. Afraid. Alone.” You do not say: lonely. But you are. Even with so many friends, you are lonely.

“And how do you feel about being sad, worried, afraid, alone?” asks the voice.

She can’t do much more than ask questions, but answering them gives you temporary relief.

At last, the acquaintance who became a friend at the party – your 5,000th friend – becomes a lover. You explore one another’s bodies and minds. Drunk on the intoxicating otherness, you let go of yourself like a child letting go of a balloon, peacefully watching your carefully maintained and delineated self float up into the sky and disappear.

You turn off for days at a time, lost in one another. You forget who you are. You say the same thing as your lover at the same moment. You listen, and feel that you are hearing your own inner narrative spooled out. You no longer need to say “me too, me too”, because it is understood.

At last, after many days, you change your relationship status on the network. A flood of congratulations follow. You feel loved, by your beloved and the network. You are together.

Is love a good thing, or a bad one? And myself, what about that?

This story was originally commissioned by, and broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

The Matchmaker of Hendon - a short story

My mother was a spinner of tales both tall and long. There was the story of the Tailor’s Tallit, which proves that a garment can be too much admired, the legend of the Bencher of Babylon, whose words may be read, but never spoken, and the tale of the Herring Bride and what became of her one true love. But these stories were not her best. She told her best story only twice: once to me, when I was a child and once to my own children, six months before she died. It was the tale of the Matchmaker of Hendon, the finest matchmaker in the world.

My mother was a spinner of tales both tall and long. There was the story of the Tailor’s Tallit, which proves that a garment can be too much admired, the legend of the Bencher of Babylon, whose words may be read, but never spoken, and the tale of the Herring Bride and what became of her one true love. But these stories were not her best. She told her best story only twice: once to me, when I was a child and once to my own children, six months before she died. It was the tale of the Matchmaker of Hendon, the finest matchmaker in the world.

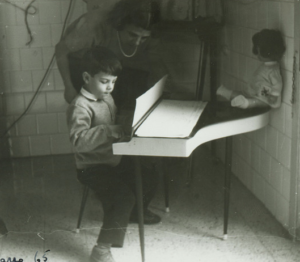

Matchmakers, my mother told the children, used to be more plentiful than they are now. It was, she sighed, a time when concern for one’s place in heaven was greater than today. For do we not learn that one who makes three successful matches guarantees thereby her seat in the world to come? Yes, there were matchmakers for the religious and the not-so-religious, for the Zionist and the Chareidi, for the Liberal, the Progressive, the Satmar and the Gerer. Not like today. In those days, to be the best matchmaker in the world, you really had to be something. You’d think, then, that the Matchmaker of Hendon was maybe raised and schooled in the art? That she trained with the great matchmakers of Paris, Jerusalem and New York? Not so. In fact, for many years she taught the piano to children.

“Like Zeida?” my children interrupted.

“Yes,” replied my mother, “like your grandfather, the Matchmaker of Hendon was a piano teacher. Now, do you want to tell the story or shall I?”

Day by day, young people passed through the Matchmaker’s home, sullen or studious, reluctant or eager. She saw that her role was not simply to teach these youths to strike the keys, but also to find the music which was most suited to them. And as her pupils grew to adulthood, she began to see patterns not only within each student but also between them. She made her first match between two of her students, then between a student and a friend’s child. As time went on, she began to discern suitable matches between people she had merely glanced, or spoken with for a few moments. It became obvious that she possessed a gift.

The Matchmaker of Hendon, we may note in passing, was herself unmarried. She came to feel that this gave her an ‘ear’ for matchmaking, just as one can more truly appreciate music if one is not humming a contrary tune. And so, over time, she came to be known as a talented matchmaker.

***

My mother paused.

“So far,” she said, “so what?”

My children blinked.

“Yes,” she said, “so what? So she’d made a few matches. No big deal.” She waved her hand airily. “Who hasn’t made a few matches? That just made her a matchmaker. Not the finest in the world. No, it took something else to win her that title. But eh, I don’t know if you’re really interested in this story. Maybe you’re tired?”

Once the clamour died down, my mother continued.

The Matchmaker of Hendon’s most celebrated case concerned the son of a certain Rabbi. This young man was bright, pleasant, learned in Torah, gentle of heart and neatly-trimmed of beard: all that a bride could wish. But he was marred by a peculiar affliction. He perspired. All men perspire, of course, but this youth was exceptional. In general not inclined to sweat, when he became interested by a young woman moisture poured from him, and with it a pungent and unappealing smell. The more attracted he was, the more foul the scent. The odour, which was equally uncontrollable by lotion, cream or pill, was enough to deter any woman. In desperation, he sought out Matchmaker of Hendon and pleaded for her aid. After he left her, she sat, as was her habit, in a chair overlooking the window, stirring her tea very slowly, sipping with very small sips, and thinking very deeply indeed. At last, decisive, she drank the tea to its dregs, stood up and made a single telephone call.

Three months later, the malodorous young man was married. At the wedding, the guests naturally declared that the groom was wise and learned, and the bride beautiful and virtuous but, in truth, only the virtue and wisdom of the Matchmaker were fully discussed. The bride was attractive, kind and gentle, marred by only one tiny flaw. As a child, she had fallen from a swing onto her nose. Its appearance was not damaged, but the blow had deprived her forever of a sense of smell. All odours were as one to her, neither pleasing nor displeasing. When, ten months later, the couple gave birth to a baby girl, she was of course, named for the Matchmaker.

After this, the Matchmaker of Hendon had no need to seek work. From Argentina and Brazil, Australia and South Africa, Israel, France, India, Portugal, Russia and Abyssinia, parents and children sought her aid. And the wider her circle of clients, the more perfect her matches became, each one more inspired than the last, until the people of Hendon began to declare that she had been given a part of the matchmaking skill which the Holy One Blessed Be He reserves for Himself.

***

“Now,” my mother said, lowering her brows and glaring darkly, “perhaps the Matchmaker became too proud and needed to be taught a lesson. Or perhaps someone else was jealous, and cast the Ayin Hara on her. The Evil Eye is real, you know, so you must always wear your red hendels, no matter what modern nonsense your mother tells you.” The children held up their left wrists, displaying the red threads tied around them. My mother nodded, satisfied. “Very good. The Matchmaker of Hendon wasn’t so clever, which might explain what happened next.”

Now the Matchmaker of Hendon’s name had become an incantation in the minds of the people. No one ever came to her single and left without their perfect mate. No one. It came to be believed that she could not fail. But when such a spell is woven, it only takes one failure for the entire vision to be destroyed. And so, upon a day, a new client came to call.

This young man had been one of the Matchmaker’s piano pupils. In fact, he brought several pieces of his own to play for her. As he began, the Matchmaker of Hendon reflected on how charming he was, his playing still shy, though much improved, his broad shoulders slightly hunched with nervousness. Yes, she thought, she would have no difficulty finding a suitable girl. She was touched by his pieces, by their simplicity, humour and gentle emotion. When he had finished playing, she told him so. Their discussion lasted several hours.

The Matchmaker of Hendon was a woman of regular and methodical habits. She worked for six days, and on the seventh she rested. From 8am to 4pm, with half an hour for lunch, she met clients and arranged matches. At 4pm, she took a walk around Hendon, to exercise her limbs, buy her groceries and, perhaps, encounter some grateful parent along the way (for modesty was not one of her primary virtues and she enjoyed receiving praise for her work). At 5pm she drank tea, very slowly, and considered the clients she had met that day. From 6 to 7 was her dinner hour. At 7pm she spread her accounts wide, and sent out her invoices. And from 8.30 to 10pm she received telephone calls informing her of the success of the meetings she had arranged. Her life went forward as rhythmically as the sweeping arm of the metronome. It was some surprise to her therefore to find, when the young man left, that her hour for walking in Hendon had already passed, as had her hour for tea. But, she reflected, if she could not interrupt her routine for an old friend, when could she?

The following day, she set to work on behalf of the young man. She selected a girl. She arranged a meeting. The meeting took place a few days later. The girl telephoned that evening: she had been enchanted, could scarcely wait for the second meeting, thought he might be the one. The young man telephoned shortly afterward. He inquired after the Matchmaker’s health, and asked whether she might be interested in looking over some new piano books. Yes yes, but the girl, what about the girl? Oh the girl had been fine enough, but not for him.

The Matchmaker frowned as she replaced the receiver. It had been over three months since she had had to arrange a second match. Her first choices were usually faultless. But no matter, she would make another attempt. That evening, as she ate her customary slice of plava cake, she found that she was drumming her fingers on the tabletop and thought that, in their rhythm, she heard the faintest sound of laughter.

The second girl would not do either. Nor would the third. Nor the fourth. It was not that they did not like him. But he appeared to be seeking something which none of them possessed. The young man became a regular visitor in the Matchmaker’s house. Together they agonised over possible choices. They played the piano while debating the qualities of a certain girl from Bratislava or another from Sao Paulo. They swapped sheet music while passing suggestions back and forth of experts they might consult. They agreed, each time, that the next choice would be perfect. But each time it was the same: the young piano player would not settle on a match.

He became notorious in Hendon. Other young people came to the Matchmaker’s door, found their allotted partner, and departed content. This boy, the people said, would reach 120 before he was satisfied with a girl. Perhaps, they murmured, all was not well with him. Perhaps his desires were not as the desires of other men. Or maybe the Matchmaker of Hendon had lost her gift. One or two young people began to seek advice from other matchmakers. One or two became six or seven, then fifteen or twenty and at last the rumours found their way to the Matchmaker’s ears.

She was shocked. This would not do, she thought. It was not orderly. Her life, which had proceeded as smoothly as a sonata, as regularly as a rondo, for so many years, had become suddenly discordant, filled with faulty fingering. She decided challenge the young man regarding his behaviour. She telephoned him that evening, at the appropriate hour. But she found the conversation rather difficult to begin; they had so many other things to discuss. At last, she blurted:

“Are you experiencing any emotional difficulties?”

The line was silent. The Matchmaker could hear the young piano player breathing, softly.

“Not as far as I’m aware,” he replied.

“Then,” she said, banging her hand on the table, “why have you not yet chosen a girl? I have found you ten and ten times ten! Are you sure you are quite well?”

The line became silent again, the young man’s breathing slow and steady. The Matchmaker looked around her quiet, tidy home, taking in the lace tablecloth and the polished brass bell on her mantelshelf. She felt suddenly afraid of what she had done.

“Perhaps,” he said, “I love someone already.”

The Matchmaker thought for a moment that her telephone was faulty. There seemed to be a ringing on the line, or in her ear. She shook the handset and said:

“Hello? Hello?”

“I’m here,” the young man said. “But I must go now. I’ll see you tomorrow. For tea.”

The next morning, the Matchmaker awoke angry. When she opened the curtains, she tugged too hard, and the pole fell to the ground. When she telephoned, she dialled seven wrong numbers in succession. In frustration, she picked at the beads on the cuff of her blouse, pulling off first one, then another, until a small shining heap was piled on the table and she realised the she had ruined the garment. She let out a cry. It was, she thought, too much. Imagine visiting a matchmaker when he was already in love! It was an insult to her profession, an insult to the girls she had found for him. Why, it was no wonder she was angry!

When she returned from her Hendon walk that afternoon, her spirits were not improved. The exercise had only increased her annoyance so that, when she approached her home and heard the unmistakeable notes of piano-playing falling from the open window, her anger ignited into fury. Even if she did leave her door open, how dare he enter her home? Play her piano? Pretend to be something he was not? She burst into her living room and began to shout. The music was stronger. The young man’s head was bowed over the piano; he simply continued to play. She saw that the piece was written in his own hand, and its notes were more than words. And as he played, she understood. And when his playing was done the room hummed, resonating where there had once been stillness.

“Whom do you love?” she asked, though she already knew.

The young man turned his head to her. And upon his face was a smile, and in his smile she read the answer to her question. And she knew that her answer was the same as his. And she began to weep.

“Children,” my mother said, “they loved each other. What joy! But what a catastrophe! Whoever heard of a matchmaker falling in love with her client? The Matchmaker of Hendon was past her middle years, but the young piano player was just a boy of twenty-two. They despaired as soon as they understood the truth, for his parents would never accept it. And without help from his parents, how were they to live? The people of Hendon would not trust a matchmaker who had married her young client. The pair tasted sweetness and bitterness in the same bite.”

My mother paused. The children grew impatient.

“What happened then, Booba? What happened then?”

My mother looked at the faces of the children. Her eyes were tender, as soft as water. She opened her mouth to speak and closed it again.

“What happened then, Booba?”

My mother smiled a strange and unexpected smile. She spoke quickly, as though trying to utter the words before she heard them.

“They were married, of course. They found that all their friends and family were far more forgiving than they’d expected. In fact, the Matchmaker became even busier than before, because now, of course, she was happily married herself. Yes, they were married for years and years and had children and grandchildren. The grandchildren were just like you except not quite so beautiful or so clever. Now, who wants rogelach?”

The children yelled and raised a forest of hands.

I stood in silence. I had not remembered the tale ending so abruptly.

***

Later, after the children were in bed, my mother and I drank tea together.

“Mummy,” I said, “how does the story really end?”

“What? What story?”

“The story you told the children, the Matchmaker of Hendon.”

My mother frowned.

“I told you how it ended. They got married and lived happily ever after. Don’t you know a good ending when you hear it?”

She took another sip of tea.

“But when you told it to me years ago, didn’t it have a different ending?”

My mother placed her cup upon its saucer.

“And what do you think that was?”

“I don’t know. Something different. More sad. More true.”

“Well.” She rubbed her brow. “I’m very tired boobelah. Another time, maybe?”

I took her hand and pressed it, inexplicably determined to hear the end.

“No,” I said, “tonight. Tell me tonight. Please.”

She made me wait until she was in bed, her lamp lit, pillows around her.

“So, my child, the Matchmaker of Hendon was in a terrible position. What could she do? If they married her career would be over, and he was in no position to support her. If she failed to find him a match, her reputation would be ruined. There was only one solution.”

“What did they do?”

“What do you think?”

I shook my head.

“They talked through the night, but all their plots and plans led back to one solution. She proposed it, in fact. He refused for seven days. Each time they spoke, she insisted it was the only course. Each time, he refused. But on the seventh day, he saw that she’d become weak with sadness and, in despair, agreed to her proposal.”

“But what did they do?”

“She found him a girl, of course. What else could they do? If they married, how would they live? He protested; he was younger and more foolish. He said they would find a way to be together, that love would find a way. She smiled and touched his cheek, but she knew in her heart that love does not make a good match. A good match needs a good matchmaker.

“So she chose a girl for him. A perfectly acceptable, pleasant young woman. And for love of the Matchmaker, he married this other girl, although until the night before his wedding he begged her to reconsider. The guests at the wedding repeated stories of the Matchmaker’s prowess, and her livelihood was saved. But you know,” my mother leaned up on her elbows, “they said that after that she lost her skill, little by little. She’d lost a sense for it, you see. Or maybe she’d betrayed whatever power it was that gave her the gift. Her matches started to fail. She would introduce dozens of couples, with no success. One or two of the matched she made ended in,” my mother lowered her voice, “divorce. Her reputation went, for all they’d tried to save it. She died broken-hearted and empty-pursed. But, though her gift failed at the end, she had made her three matches, and three times thrice three and more.” My mother laughed, a short, rattling bark. “That woman had enough merit to get all of us through the gates and into the world to come.”

“And the young piano player and his wife?”

“It took the wife,” my mother’s mouth worked, “it took her years to understand where her husband’s affections lay. And when she did, what could she do?” My mother sighed. “She had her life. She simply carried on.

“The young piano player became a piano teacher, like his beloved. He and his wife had a daughter and they lived,” my mother closed her eyes for a long moment. “They lived with a certain measure of happiness. No one can say that they did not. And the piano player who became a piano teacher grew to be an old man, and passed to his reward. But I think,” my mother placed her hand on mine, the skin paper-thin and dusted with liver spots. She squeezed my hand. “I think he always loved her. Until the day he died. And I never told him that I knew. No, I never told him.”

She turned her head toward the pillow. Within a few seconds she was asleep.

(This story was originally published in the x-24:unclassified anthology.)

All The Sorrow That Came After (a short story)

This story first appeared in The New Statesman in May 2012

“And was Jerusalem builded here?”

William Blake

1. Oxford, England, April 1221 Anno Domini

Edric watches her in the marketplace. That is where he first sees her. She is choosing fish and arguing with the merchant about the freshness of the catch. She’s right; here in Oxford, with the river running just on the outskirts of town, there’s no excuse for fish that’s less than perfectly fresh. These have the dull skin of yesterday’s haul. She argues sharply but merrily.

“Haven’t I got eyes?” she says, “haven’t I got hands, to give this fish a prod and see that it’s dry? I’ll give you a farthing for it, no more.”

“Lady,” says the fishmonger, “at that price I’d as well throw it back in the river and hope it spawns again.”

She’s not deterred.

“If I bought it from you at a penny, I’d be as good as throwing my money into the river!”

Edric watches her from behind. She’s wearing a dun brown dress with white collar and cuffs, freshly laundered. Her bottom is round and neat, her hips broad. He’s newly arrived in Oxford from Coventry, hasn’t been here longer than three months and he’s only touched one girl’s cuckoo’s nest before. Her hair is black and her skin is golden like wheat. He wonders already what her breasts look like, what colour the hair between her legs might be.

She turns her face to the side, holding her forehead to indicate her frustration with the fishmonger. Edric’s not disappointed by her features. A wide mouth, a high brow, a small nose, a darting quick brown eye. He’s already preparing an opening line – maybe he’ll just ask her what she’s planning to make with that fish – when, as if she’s planning to walk off in disgust, she turns round. And he sees the white patch sewn onto the front of her dress.

2. “There being unfortunately no sufficiently visible distinction between Jews and Christians, there have been mixed marriages or less permanent unions; for the better prevention whereof, it is ordained, that every Jew shall wear on the front of his dress tablets or patches of cloth four finger-lengths long by two finger-lengths wide, of some colour other than that of the rest of his garment”

Statues of the Realm c 1215

When I read this, I measure it out. Sewn onto my clothing, curved around my body, it would go from neckline almost to my waist. There could be no concealing it. That’s the point of course.

These patches and symbols and even special hats for Jews were common in Europe. When Reinhard Heydrich, one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, introduced the yellow star with the word Jude in the centre for the Jews of the Reich, he wasn’t inventing something new. He was bringing back an old tradition. A piece of Medieval Europe; like banners and pageantry and guilds.

3. Edric says nothing to her. He watches her as she bargains a little more – comes away with the fish for probably half of what it’s worth. He thinks to himself – how Satan comes in with these little thoughts, how he worms his way into the heart like this – that it can do no harm to appreciate a woman’s form, even if she is a Jewess. He is only a lad of 20, after all. She is, perhaps, a little older – 22 or 23. Her breasts are outlined by her dress, round and soft and high.

But it does do harm, of course it does. She notices him staring. She catches his eye. She smiles. He’s not a bad-looking lad himself, as it goes. He had a pox when he was 16 left him with a constellation of pockmarks on one cheek, but the other is fair, and he’s strong in the shoulders and the arms. He thinks about how he could lift her up with one arm maybe, and how she’d squeal and how he’d like it if she did. He smiles back at her and thinks: she doesn’t look like a demon to him. And if there are horns under her hair they’re well-concealed.

He says: “you got a bargain with that fish,” and feels full pleased with himself for his Christian generosity in making a pleasant remark to her just as if she were a good woman of Oxford like any other. There’s no need to treat them like beasts, after all.

She looks at him, impassive. Blinks once.

“Sorry,” she says, “I don’t speak to Christians. You might bring peril to my soul.”

She smiles, with such naughty glitter to her eyes. There are dimples in her cheeks. It is the dimples that delight him. He cannot but say more to her, linger there a little in the market, though he hears a tut from one or two of the old women. After all, what harm is there in conversation?

“What’s your name?” he asks at last.

“Jewess,” she says, “why would you need another?”

She is nothing but cheek. He wants her sorely.

“No but tell me,” he says, “tell me your name.” He has no more cunning in him than this.

“Hanna,” she says, “daughter of Eleasar the Leech.”

“The doctor! I know him.” Edric’s college master has directed him more than once to the Jew doctor for cures. “His powders for griping of the guts are… they’re very effective.”

She smiles, a swift and natural smile, no artifice or teasing.

“I will see you again, then.”

4. The Jews, they say, were brought to Medieval England by William the Conqueror, although there is some evidence that some Jews were here before that he certainly swelled their numbers. He gave them the King’s protection, proclaiming in 1070 that he would “treat both their persons and their property as his own”. The Jews were the property of the King; no man could harm them without harming the property of the King, and no Jew could travel or settle except where the King willed it.

5. In the cool chapel of the Augustinian House, Edric kneels before the statue of the Blessed Virgin. He presses his forehead to the flagstones. He mutters a prayer.

“Keep me far from temptation and lead me not into evil. I know it is wrong, Blessed Mary I know she is poison, I know she is cursed, please stop me wanting her.”

Even as he says the words, he thinks of the thick wet feel of her, as if it were poison dripping from between her legs, and Jesu help him he is still full of desire.

It had not been hard to find reasons to visit the Doctor. The buildings of the Augustinian House are damp. Someone is always sick with a fever or an ague or a cough that will not lift and is it not his Christian duty, his charity, his compassion, to walk through the muddy streets to have the leech mix up a cure for them? Like Adam accepting the apple, he knew what he was doing.

In the warm, close back room of her father’s shop, while the old man mixes his potions and grinds his roots and herbs, Edric and Hanna talk. She is clever, he finds, and her conversation is interesting. She reads – this astonishes him. She tells him that Jewish women learn to read just like the men – that on her wedding day a Jewish woman might be given a hand-written little stitched book of Psalms. He finds that he likes her. She has met half the men in the Augustinian House when they come for cures and she makes funny little mocking impressions of them. She tells him her worries for her father, if she were to marry and leave him alone. He tells her of his parents in Coventry – so proud that their son, their only son, has been ordained a Deacon – eager for him to find a wife.

It is there, when their conversation drifts to silence and they look at one another, and his heart is thumping in his chest and she shifts a little towards him, it is there with her father grinding spices in the next room that he first kisses her and she kisses him.

They walk in the quiet forest in the morning when she goes to gather plants, when his morning prayers are finished they meet there. And they talk, and she holds his hand. And pushed up against an oak, he lifts her skirts and touches her with his fingers. To their great pleasure. He would have gone further but she shakes her head and laughs and says:

“I must have some virtue for my wedding night.”

He is amazed, charmed, puzzled, excited. These things must show on his face.

“After all this,” she says, “did you still think a Jewess is a devil woman?”

She kisses the top of his head.

“It is the same,” she says, “your laws and our laws are the same. Except that yours are more… newfangled than ours. We keep to the old ways, and you have let them go. It is not so different.”

God help him, when he presses his face to the cool of the chapel floor and begs the Virgin to protect him and change him, and take away his unnatural desire, God help him, he thinks she may be right.

6. My grandmother’s cousin and her children were evacuated in the Second World War to a farm in the north of England. One day, my grandmother’s cousin found the farmer’s wife examining the children’s heads, running her hands through their hair, searching out the scalps with the pads of her fingers.

“Have they not come in yet?” said the farmer’s wife.

“What?” said my grandmother’s cousin.

“The horns,” said the farmer’s wife.

Those children are alive still – they are my parents’ age.

7. The Virgin does nothing to protect him. He tries, for a few days, to stay away. It is fire in his veins.

Something is grievously at fault with him, he knows it. In confession, at last, after several days, he tells the priest that he is filled with lust for a Jew-woman. Behind the screen, the priest mutters that Satan gives them wiles to tempt good Christian men, and he is to devote himself to the contemplation of the blessed Virgin. He says his penances. In the aisles of the chapel, he knows which priest it was who heard his confession by the unblinking stare he gives him – it is Thomas, a hard and godly man. Edric casts his eyes down not to meet Thomas’ gaze.

That evening, the Virgin fails again to help him or protect him. One of the lay brothers develops a powerful cough, so wheezing and so deep that the man can hardly breathe. Someone says – is it Satan who says it? – “this cough is a danger. Some man must go to the apothecary to bring a cure.”

It is late, and raining hard outside. No one wants to go.

“I will go,” says Edric, “I will go to the doctor to fetch medicine.”

The others thank him. Thomas gives him a dark look and a tiny shake of the head. But Thomas does not volunteer to go in his stead. The rain is very heavy, after all.

Hanna is angry with him at first, for staying away so long. She shows it by talking to him like any other customer.

“Yes sir,” she says when he tells her father the symptoms of the lay brother, “Doctor Elasar will make the treatment now, a syrup of honey and herbs. You may wait here until it is ready. Sir.”

“Will you not wait with me?”

The idea that he might have lost her now makes his heart cry out.

“Why no, sir. I do not wait with customers, only with my friends.”

Elasar looks between the two of them, his eye shrewd.

“Daughter,” he says, “I have forgotten where you put the herbs I need for this tincture. Come and help me with it and leave this good man in peace.”

“Why that is what I wanted to do, father.”

They leave him there, waiting alone. The mere sight of her has stirred him up again so much that he cannot bear the thought that he will not touch her tonight.

After a little while, she opens the door to the room with a fire where he is waiting.

“My father would have me ask you if we can offer you some food, or a cup of ale, while you wait. Sir.”

The father is not with her. He leaps to his feet and, before she can protest, or move, he kisses her, kneading at her breast with his hand. She kisses him too, for a few moments, then angrily pushes him away.

“Is that all I am to you? Some Jewish whore you can grope at while you wait for medicine?”

“No,” he says, “no no no.” And his heart breaks open. He tells her the truth. “I think of you all the time. I prayed to the Virgin Mary to make me forget you but I can’t forget you, you are all I want.” He says it again, because he has noticed for the first time that it is really true. “You are all I want.”

She looks at him, searching out his face for the marks of truth. There are angry tears in her eyes.

“I cannot marry you,” she says. “I can marry only a Jewish man. My father has picked one out, I think.”

He smiles. “Did I ask you to marry me?”

Her eyes are black, and a tiny hint of merriness is back in them.

“I expect you will,” she says.

They talk on. By the time the tincture is made, their quarrel is over. She wants him too, is the clear thing. With his short, wiry frame and his kind, worrying head.

Somehow, yes, this.

Elasar looks between them again when he brings the tincture in. It is impossible to keep such a thing out of one’s eyes. Elasar shakes his head, sadly.

“It is forbidden under your laws, you know,” he says to Edric.

Edric’s heart is too glad to hear anything. She wants him too: that is the whole of the law.

He and Hanna kiss a long goodbye on the shining dark streets of Oxford, the rain having passed. As they part, both breathless, she whispers to him:

“The Virgin Mary was a Jew woman too, you know.”

He has never heard anything so obscene as these words.

8. The Jews were known mostly as Christ-killers. It was the presence of the New Testament, of course, that book which carried hatred of the Jews from town to town, from nation to nation, until it had spread over half the Earth. It was reported widely that the Jews killed Christian children in mockery of the crucifixion. That they drank or ate their blood. Other Kings had not been so magnanimous toward the Jews as William the Conqueror. They were accursed of giving Richard I the ‘evil eye’ at his coronation, leading to a great massacre of the Jews across England. In 1190, the Jews were murdered in King’s Lynn, in Norwich, in Stamford, in Colchester, Thetford, Bury St Edmunds and York. Such outbreaks became, if not routine, at least regular.

9. There’s one thing left to do. She doesn’t ask him to do it, but he knows that it has to be done. Although Eleasar offers to help him, he decides it is better to do it himself, alone. Early one morning he wades naked, waist-deep, into the River Isis and stands there until he can no longer feel his feet or his legs or anything above them. He walks out and quickly, with the sharpest blade he has been able to find, pulls his foreskin taught and slices at it, in one motion. The pain is blazing loud even despite the rudimentary numbness. He bleeds more than he’d expected and is grateful for the salve Eleasar gave him to smear on it. For two weeks, he keeps to his room in the Augustinian House, saying that he had taken a wound to his thigh when falling in the woods. They bring him food and water and he feels a little guilty knowing what he is planning to do.

He leaves the Augustinian House with all appearance of sorrow. The Lord, he said, appeared to him in a vision and told him that his great calling was not to be a deacon and a student but to leave on other work. Thomas, and some of the other brothers, look suspiciously at him. But what can they do? He is a free man, he thinks, and can go where he likes and do as he pleases.

He goes to Hanna’s house in the Jewish district. She has been waiting for him. He tells her that it’s done. He’s still sore, but the wound is healed clean. There’s no going back for him now. As he tells her, a terrible fear strikes him that perhaps she will not have him, that she would tell him now to go away.

But she does want him. She feared, herself, that he would not come back, that she would see him again in the street in months to come and he would mock her and call her a Devil Whore to cover up the tenderness that had been between them. They are both afraid. But the yearning is greater than the fear. She kisses him with kisses of her mouth, and his love is sweeter than wine. And within the month, when he is fully healed, they are married.

Now, they do have some months of happiness, this is certain. There are sweet mornings waking together and making love tenderly, and her stroking his face as his beard begins to come in fully, and the things she teaches him of her ways and faith and the secrets of the herbalist, and how she sits on his knee while he shows her the Latin grammar and tells her about Coventry. We cannot deny that they had some months together.

But in spite of the holiness of the confessional, in the end Thomas will speak eventually to Matthew, and Matthew to Simon, and Simon to Roger, and so the word will come to the church authorities that a Christian man had taken on the Jewish faith and married a Jewish woman. And so one morning, while Hanna is at the river bathing, twenty of the Sheriff’s men with cudgels come for Edric. They find him working on a pot of salve for bruises. And he shouts to the neighbours to warn Hanna and tell her to run, as the men take him down and cover his face with a sack.

10. This story is a true story, at least in its bones. It is recorded in various chronicles, along with the many other massacres and murders of Jews in Medieval England. During the period that I was reading about it in the library, I got chatting to another woman, also working in the library. I told her about the Jews put to death in various ways under the various Kings of England.

“Well,” said the woman, “you have to understand these things in their historical context.”

I found I was blindingly angry when she said this to me.

“I don’t think the people put it in its historical context,” I told her, “when they were being murdered. I don’t think they said to themselves: well, I must understand the society and cultural forces which made this happen. I think they suffered, and died.”

I suspect this woman felt that I was insufficiently magnanimous. Not filled with enough Christian love and charity.

11. Edric is brought to trial before the archbishop. They show him a cross with the Crucified Lord upon it. Edric remembers his boyhood, kneeling before a cross like this, kissing it with the lips that have kissed Hanna again and again. He wants her now so that his body aches to hold her. And he imagines her as she must surely be, in the little pedlar’s cart belonging to her uncle, on her way to London, concealed under the blankets and the apples. Safe, maybe. And perhaps he will see her again.

“Repent,” says the archbishop, “throw off your sin and shall you not be forgiven?”

He could say it now. It would be simpler. He could say: I recant, I accept the Lord Jesus into my heart. He could do that and perhaps they would believe him and perhaps let him go and then maybe under cover of darkness he could steal away to find Hanna in London and snake his arm around her waist and hear her chuckle soft and low. And maybe they would travel somehow to Paris or Amsterdam or even Spain where they could be just another Jewish man and his Jewish wife, her belly full of their Jewish children. This is what he wants, this simple thing.

There comes a time when the heart is so certain of what it wants that the tongue cannot be persuaded not to utter it.

“I don’t want the new-fangled law, I am for the old ways. I don’t follow the teachings of Jesus. He was a liar like his mother Mary – surely she lay with a man, and when she fell pregnant lied that the Lord had got her with child. I am a Jew now. A Jew like those others.”

It is the truth. Does it not say in the Gospel of John, “the truth will set you free”?

12. The archbishop is Stephen Langton. He had himself been the subject of a great quarrel between Rome and England – King John refusing to recognise him as Archbishop of Canterbury, Pope Innocent insisting. The result of the quarrel had been a five-year interdict: the Pope refused to allow any birth or marriage or mass to be celebrated in England.

An interdict is a bad business for the souls of the English. It cannot be risked again. For a good Christian to insult the Virgin Mary in this fashion is to bring the wrath of God – and the Pope – upon the land. There is only one possible ending.

13. The chronicles are a little unclear and contradictory on how it happened. Some say it was fire, and this is the majority view. But Matthew Paris’ vivid account tells it differently. He has Stephen Langton cast out from the church the English deacon who had loved a Jewess with an unlawful love. And then Sir Falkes de Breauté, a local knight who, Paris tells us, was “ever swift to shed blood”, was so horrified by the conversion of a Christian man to Judaism and by the words he spoke against the Virgin that he: “at once carried him off and swore ‘By the throat of God! I will cut out the throat that uttered such words,’ and dragged him away to a secret spot and cut off his head. The poor wretch was born at Coventry. But the Jewess managed to escape, which grieved Falkes, who said, ‘I am sorry that this fellow goes to hell alone.’”

And perhaps it was fire. And perhaps it was the sword. But we know that the man whom I have called Edric, for his name is long forgotten, died by the hands of the church and those who sought to protect its honour. And the Jewess whom I have called Hanna, for her name likewise is not recorded, escaped. Perhaps we can imagine her, there, among the apples, weeping for her husband as the cart travels the rough miles to the coast. And perhaps he died knowing she was safe. And maybe there was comfort for her in her womb, in some new life stirring there. And maybe he knew this when he died. Maybe. Perhaps.

Naomi Alderman’s new novel The Liars’ Gospel will be published by Penguin in August. Many of the historical details in this story are taken from Robin Mundill’s excellent The King’s Jews.